“Spiritual fatherhood has nothing to do with power or control. It is a fatherhood of compassion. But the father of the prodigal son is not concerned about himself. His long-suffering life has emptied him of his desires to keep in control of things. Can I give without wanting anything in return, love without putting any conditions on my love?”

―Henri Nouwen, The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming.

The plan, according to the experts at Roma’s treatment center, was for Roma to move to a halfway house after his 30 days of rehab, where he would live for four to six months. He was required to get a job and pay his own rent. The same plan he aborted the previous year. Roma had given his permission for his therapist to share all information with me. Drugs in his system when he entered detox were alcohol, marijuana, and this time, he had added meth.

If there was anything for which to be thankful this time, his use of meth had immediately scared him into urgently seeking help and checking himself into rehab again. His counselor said he was a model patient, truly eager to get clean. She felt he had a great chance of succeeding.

Blah, blah, blah. I had heard it all before. I had been encouraged before that change was imminent. By this time, I had built a wall to protect my injured heart. I was afraid to be hopeful. But, of course, my hopes once again soared.

He confessed to me that the meth had been a bad mistake, “I don’t know why I tried meth, Mom.”

“Roma, were you sleeping through the drug films in high school health classes? Meth? Really Roma? What were you thinking? Meth rots your teeth!” I tried to appeal to his considerable vanity.

Even though I had resolved to let Roma have his way (as if I had a choice) and not interject my will into his prodigal experience, I intervened when Fred recommended a Christian-run halfway house after Roma’s 30-day treatment. Even though I had never met Fred, I trusted him completely, as I had trusted Nancy long before I met her. There could be no doubt that God had brought both of them directly into our story for a reason.

Fred was totally bonded with Roma after God connected him twice by astounding “chance meetings,” on a sidewalk in Delray Beach and at a Celebrate Recovery meeting a year later. Roma asked him to be his sponsor in CR. Fred told me that these God experiences with Roma had changed his life. I understood, because God had transformed my own life by this precious, yet wildly frustrating boy. Fred wasn’t the first, or last, person to acknowledge that they had seen God work powerfully in Roma’s life. Fred took his God-given ministry of Roma’s spiritual protection very seriously, inviting him for dinner with his family, spending time with him, and in the process, falling under Roma’s spell.

Fred was fascinated by this young man who God had called him to love. He would call me occasionally to update me on progress. “I just love this kid,” he would tell me, surprised by the level of his devotion to my son. “He’s so interesting and smart. He can talk about anything. He seems very educated. Did he go to college?” When I didn’t answer right away, he asked, “Is he well educated?”

“Well. . . he did spend five years in high school,” I couldn’t resist. “Almost five years,” I corrected myself, recalling the expulsion from school, six weeks before graduation. When had I become droll about Roma’s failures? When I learned it was easier than despairing about the challenges.

Roma’s extra year of high school had nothing to do with him being a slow learner. He emphatically was not. It was a strategy to give him more time to get ready for life, whether college was the next step, or training for a job. It was a holding tank to keep him busy and safe, while preventing boredom. Early trauma in children’s lives can stunt their emotional growth. Roma didn’t have the kind of maturity most kids his age possessed, even though he had lived enough in his short life that his experiences made him eons older and more savvy. Three years of public high school revealed that a fourth would not be sufficient for him. Two more years at a military academy were a perfect fit for Roma—with the structure, the camaraderie of the boys and men, and the sports program Fork Union offered. He thrived as a cadet and enjoyed his experience immensely. One of his teachers, a retired Army officer, as most teachers were, sent me a note saying, “Roma is a diamond in the rough.” I was thankful he was being polished where his value was noticed and appreciated.

The same way Roma had ingratiated himself into life at Fork Union, and life at our house and community, for that matter, he embraced all the halfway house had to offer. He befriended and endeared himself to all members of his new group home, from the directors and counselors to the other residents.

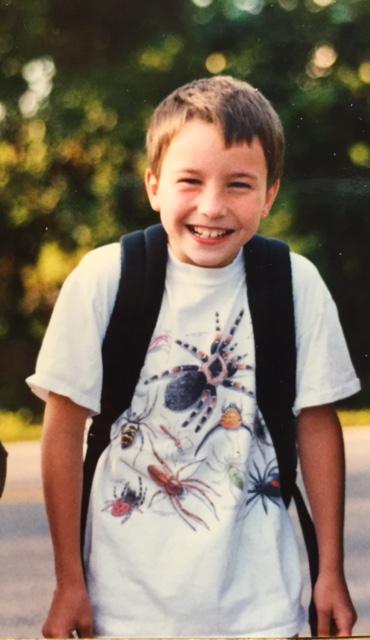

In fact, Roma’s ability to endear himself to people was in his hard wiring. I couldn’t miss it at first sight when I picked him up in a church basement for our hosting experience in November 2001, when he was only seven. That personality, that warm charm was an enviable asset. He always put himself out there, with everyone he met, whether he was inviting his new elementary teachers to his little league baseball games, to knocking on his new neighbors’ doors, just to say hi, to inviting a neighborhood bully to be his friend. He was always cultivating relationships, collecting hearts. He held nothing back. I had two nicknames for him when he was little, Roamin’ Roma, and, when he was playing sports, the Rushin’ Russian.

I am far more reserved than my Mr. Personality. I don’t want to bother people. I often thought that Roma shouldn’t bother people either, that he didn’t read social cues, that he might not recognize when to pull back, to give friends a respite from his intense personality.

“Don’t always be in your friend’s house, or they will hate you,” I would only half tease, paraphrasing Proverb 25:17. I tried to give him gentle warnings.

“Oh, Mom, they love me,” was always his perspective and answer. Roma was Roma, unapologetically. He often got a pass that other kids were denied. One of his early principals shared when he graduated from elementary school, “Roma is so special, we didn’t mind any of his mischief.” There was no denying, the boy had “gifts”!

That open, inviting personality continued to be an asset for him in his new halfway house. He had made friends and advocates, and everyone was working with him to find a job and to, perhaps, go to college, when they recognized his intellectual abilities. His counselor called me about helping him apply for financial aid. He wanted to be an EMT, that week, and training was available in the area where he was living. I told him to start saving his money to make it happen. We would help him if he first helped himself. I was still trying to not be a safety net for him, and to allow him to make his own good decisions so his success could breed more success. To let it be his decision. Or at least let him think it was his decision.

The middle of August 2015, just days after he announced on Facebook that he “never thought (he) would be sober on his 21st birthday,” he texted me to tell me he was leaving Florida and coming back to Maryland. He wasn’t planning to come home; he had plans and told me not to worry.

Then the director of the halfway house called me to explain that Roma’s leaving was not their wish. He was doing exceptionally well with their program, and they loved him. He said Roma was discouraged because his job wasn’t working out. He was a telemarketer for reducing interest rates on student loans, and he had a quota to fill. The job was not a good match for Roma’s outgoing and connecting personality. He wasn’t used to annoyed people’s rejections.

I called Roma back and tried to persuade him to stay, going against my determination to let him fail or succeed on his own. He said determinedly that he had a plan all worked out. When I tried to learn more, Roma shut me down, saying, “Don’t worry about it.”

I sent Fred a text to see if he knew about Roma’s impulsive exit plan. He called immediately, sickened by the unexpected news.

As usual, I had no power to change Roma’s stubborn recklessness. What a mercy that God had made me aware that trials were coming, and that intuition never waned. I could never despair but keep walking in the path before me.

Roma settled back in Maryland in mid-August to live only 30-40 minutes from home. “Putting himself out there” meant Roma was bold enough to ask for favors—from friends to complete strangers, and anyone in between. I could imagine Roma asking everyone he had ever known, even in the remotest sense, if he could live with them until he could find a job and help with rent.

No, Roma wasn’t shy about asking. And he wasn’t easily offended or discouraged if he received a no. His list of possible helpers was endless. Who knows how far he had gone down his check list before getting a nibble from the winner of the opportunity to be Roma’s roommate? And he was sincere about his offers of one day being a contributing member of a household.

He did not want to live with his dad and me. He was 21 and, in his never humble opinion, he was an adult. We had rules, even for adult children living at home. And our not-so-distant memory of Roma residing with us had been a strain. Most of his friends were away at college, and living independently from their parents, as far as Roma could tell.

I was surprised to learn that Roma’s new roommate was living with his mother. This little detail comforted me. If Roma didn’t think he needed his own mother, perhaps he would continue to get a bit of wise mothering elsewhere. It was always evident that Roma could never have too many mothers. All I knew is that he had a job working with a handy man. I didn’t see Roma as possessing “handy man” skills. He needed to be with people, because he did possess strong people skills. But he had a job, and maybe he would learn some skills, or learn he wanted more education.

Roma reached out to us often while living away, yet so close. I would get a surprising text saying, “Mom, look at the sunset this evening, it’s beautiful.” I thought this odd and amusing and encouraging, because I was always saying that to him, often dragging him from the TV to come out on the deck to see God’s artistry. Or when we were driving home, over the last hill, the landscape would open up and was mostly painted sky. Sometimes I would stop the car at the top of that hill so we could marvel at the beauty.

“Maaahm,” he would scold me in his boredom, “It’s just a sunset, oh my gosh, they happen every night.”

I wondered if Roma’s new recognition of the familiar splendor of the sunset made him a little nostalgic, tugging his heart toward home. Once there was a serious car accident a quarter mile from our house, and Roma, after hearing of it, called to make sure we were all safe and not involved. No one could deny that Roma had a heart the size of all of Russia. And He did love his family.

He asked if he could go with us to our lake house in neighboring West Virginia the next time we went. We agreed, cautiously optimistic, and agreed on Labor Day weekend.

Once at the lake, our extreme extrovert wanted to go to the lodge earlier than we could, to see what was happening. He rode a bike the mile and a half to the lodge to start making new friends for the evening. When we arrived, Roma came over to introduce himself to our friends, always the gentleman. By 11 p.m., we were heading home, telling him to head home on his bike soon. I texted him and he texted back, “I’m just hanging home.”

I read it as “I’m just heading home,” an auto-correct issue, I assumed. I texted him at midnight, asking if he was okay, since we hadn’t heard from him, and he was riding a bicycle without streetlights.

His last text before his phone battery died read, “I’m fine.” When he finally came home, an hour later, he defended himself by telling me he had told me that he was just “hanging here” for a while, since his new friends were still available. Roma didn’t want to miss anything. It was a golfing weekend, and he met some people who were staying in the motel. Roma, never one to miss any activity, assumed we knew he was okay, because he had told us. And he had grown unaccustomed to checking in with us. Although he was 21, I didn’t want him to drink, but he did. When he arrived home, he was intoxicated, but “still able to ride a bike,” he defended himself.

Those kinds of misunderstandings were common in our communications with Roma. He couldn’t understand why we would worry. He had told us the truth. And he was 21, he often reminded me. After our weekend together, the first in four months, we dropped him off near his new home at a convenience store. He said we couldn’t drive beyond a gate. I suspect he didn’t want us to know exactly where he was living. I was determined to allow him this freedom.

Later in the week, via a Facebook group from our lake house, I learned that Roma had made some nice friends at the lodge that night. He had left a favorable impression on adults in our lake community to whom he had talked at length that night. That shouldn’t have surprised me, but it did please me. I had been consumed with worry instead of being encouraged that he was showing maturity.

By mid-October he was talking about coming home. Home. Our home. I was reluctant because it had been difficult to share a home with Roma in the not-so-distant past. Although he had always been easy to love, it was not easy to raise a boy who wanted his freedom more than a family.

Two weeks later, Roma began desperately talking like a homesick boy. I was not eager to start the cycle again. Hadn’t God nudged me to withdraw the safety net? Was it time to run and eagerly greet the prodigal son?

In mid-October, Roma ramped up his hints that he wanted to come home. A sense of dread settled over me, as my memory was still fresh from when he was home four months earlier, and of every episode of his home stays before that. Had he worn out his welcome with his present family?

Still, something made us know that if Roma wanted to try to live at home again, we had to welcome him, while maintaining our high expectations of his improved behavior. He told me that he needed his family. We knew what Roma needed most, after God, was his family, but it had to be Roma’s idea. It always had to be Roma’s idea.

On Monday, October 19, 2015, Roma decided it would be a good idea to come home. He also decided that he would follow the house rules. He reminded me it was his idea, and I didn’t have to remind him.

He met Bruce at the church gym for Monday night volleyball and asked if he could return home to live. Bruce wanted to get assurances from Roma that he would follow our rules if he returned home to live. He assured Bruce at the church, before playing volleyball, that he would live under our conditions and that he needed his family. That evening, Roma returned home with his pitiful little bag of possessions. The prodigal son had returned. He was almost contrite. And almost contrite for Roma was a shocking and welcome condition. He sat down with us at the kitchen table, and reinforced to us that he needed his family. He wanted his family. He wanted us to go on a family vacation, like we used to do. Like a little boy, he told us he wanted to rent a big house at Holden Beach in North Carolina, like before, and the whole family go. Maybe he could invite a friend. He had it figured out this time. And it was going to work this time. I told him we would start making plans for a beach trip for the summer of 2016, like we did when he was little.

The prodigal son was home. Again. I was trying to be eager, realistic, and yet optimistic. I was trying to offer Roma grace. And surrender to God’s plan. Again.

Continue with Chapter 20